-

-

-

The Almouchiquois

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

About Falmouth - The Almouchiquois

The previous section reflects the latest published research on the 17th and 18th century Native American presence in Ancient Falmouth. We are often asked for more information about where and how these early inhabitants lived.

Summary. The Native people living in Ancient Falmouth when Europeans arrived in the 17th century belonged to the Aucocisco, a semi-autonomous band of "Almouchiquois" within the Wabanaki. The Aucocisco reportedly had 240 men (suggesting a total population around 700) before 1607. Their numbers declined due to war, disease, and emigration until they disappeared a century later. Their territory was Casco Bay—ranging from Scarborough to Cape Small—and they lived primarily along the Presumpscot River from Westbrook to Casco Bay. Unlike Wabanaki tribes to the east, they generated much of their food and trade through farming. They had one or more villages and at least one large planting ground. They also hunted and fished.

Looking for information about Native Americans in colonial Maine means taking a deep dive into confusion, contradiction, and the unknown. What few accounts we have are from European settlers who struggled with the Algonquin languages and applied European political and social frameworks to what they saw.

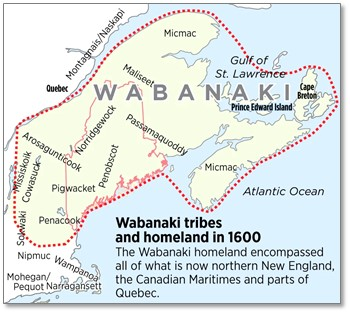

There is broad acceptance that Native peoples of northern New England and the Maritime Provinces are collectively known as Wabanaki but there are conflicting views as to the subgroups. The picture is muddied by “virgin soil” epidemics and inter-tribal warfare resulting in large-scale deaths among Native Americans during the early 17th century. This led to alliances among tribes transcending cultural and linguistic differences. There is no authoritative list of tribes among the colonial-era Wabanaki. Much of what you will find on the Internet comes from century-old publications which have subsequently been shown to be inaccurate.

For example, the Press-Herald’s excellent bicentennial series beginning with “Colony, Chapter I: Dawnland” included this graphic:

This would lead you to believe that the Native Americans living on Casco Bay when English settlers arrived were Pigwackets (Pequawket), an Eastern Abenaki tribe. Historical accounts tell a different story.

We believe the clearest picture is provided by Prof. Emerson Baker, a historical archaeologist and professor of history at Salem State University. He reasons that Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer, got it right when he treated all the people from the Androscoggin River southward along the coast to the north shore of Massachusetts as a group he called the ‘‘Almouchiquois.’’ In a 2004 paper, Baker concludes:

The Indians of coastal Maine south of the Kennebec were distinct from their neighbors to the north and should all be considered to be Almouchiquois, the peoples who ranged as far south as the north shore of Massachusetts. Deeds, treaties, and other evidence all indicate that the Almouchiquois of southern Maine had settled into distinct territories, with separate groups occupying: the lower Androscoggin, Casco Bay, the lower Saco, the Kennebunks, Wells, and Newichawannock (or the Piscataqua). These groups intermarried and allied with each other, although they seem to have remained autonomous. They also had ties to more southern and western members of their group in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Sedentary horticulturalists, women in these groups sometimes had considerable power. Some men took up residence among their wives’ peoples, making them matrifocal, if not matrilocal.

Earlier papers refer to these tribes as “Abenaki” although they are distinct from Eastern Abenaki (Western Etchemin) and Western Abenaki.

Providing historical context, in 1607 the Souriquois (Mik’maq) and Eastern Etchemins (Passamaquoddy, Maliseet) launched violent inter-tribal attacks (called the Tarratine War by the English) against the Western Etchemins (Penobscot, Kennebec) and Almouchiquois that lasted until 1615. This was followed by the plague (“Great Dying”) of 1616-19. An estimated 2,500 out of 7,500 eastern Etchemins died, while an estimated 9,000 out of 12,000 western Etchemins perished. The Almouchiquois must have suffered staggering casualties. Even after the collapse of the western Etchemin, Mik’maq raids against the Almouchiquois continued as late as 1631, possibly for food.

An account dated 1623 (but based on information probably before 1607) reads:

To the Westward of Sagadahoc, foure dayes journey there is another River called Ashamahaga, which hath at the entrance sixe fathoms water, and is halfe a quarter of a mile broad: it runneth into the Land two days journey: and on the East side there is one Towne called Agnagebcoc, wherein are seventie houses, and two hundred and fortie men, with two Sagamos, the one called Maurmet, the other Casherokenit.

Sagadahoc is the Kennebec River and Ashamahaga is the Presumpscot.

Where was Agnagebcoc? Nobody knows for sure. It was probably on or near the Presumpscot. It may have been near Lower Falls, Cumberland Falls, or Saccarappa Falls.

In 1623, Christopher Leavitt came to Casco Bay:

I found another River, up which I went about three miles and found a great fall, of water much bigger then the fall at London bridge at low water, further a boate cannot goe, but aboue the fall the River runnes smooth againe. Iust at this fall of water the Sagamore or King of that place hath a house, where I was one day when there were two Sagamors more, their wiues and children, in all about 50. and we were but 7.

He referred to Cogawesco and Skedraguscett as Sagamores.

Baker discusses Skitterygusset’s family:

Sachem Wickwarrawske, his wife Naguasqua, and their daughter Warrabita (or Jane, Jhone, or Jone) and her two brothers, Skitterygusset and Sagettawon, were one of the most powerful Almouchiquois families. Wickwarrawske’s family and their people occupied the region around Casco Bay. The eastern borders of their territory lay at Sagadahoc, the joint estuary of the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers, marking an important ethnic boundary. Living at the northern limit of native corn agriculture differentiated them from their hunter and gatherer neighbors, the Etchemin and the Micmac. Occupying an area rich in fish, furs, and timber, they engaged in intensive interaction with English traders and settlers. Situated between the English and the French, they became key players in the diplomatic and military events of the era.

Skitterygusset and his wife are also mentioned in other accounts including Willis’ History of Portland.

This leaves us with the Aucocisco (Casco) band on the Presumpscot River. Their territory included Casco Bay from Scarborough to Small Point. They were known to have a village at the lower falls. There was a planting ground at Ammoncongin (Cumberland Falls). There is anecdotal evidence of activity by Native peoples throughout Casco Bay. A shell midden on Great Diamond has been declared a historic area. (The state tends to be mum about locations of such sites to discourage souvenir hunting.)

Between 1606 and 1624, the Casco band on the Presumpscot shrank due to attacks from the eastern tribes and disease. The numbers continued to decline as the descendants of Wickwarrawske sold land to English settlers under terms affording shelter and food. By the mid-1670s, many surviving Almouchiquois had joined Western Abenaki tribes or migrated to Québec.

Then came King Philip’s War (1675-1678) followed by King William’s War (1688-1699) and Queen Anne’s War (1702-1714). The Casco band had disappeared as had most of the Almouchiquois. By 1726, Pigwackets moved into the Presumpscot River valley. Subsequent skirmishes in Falmouth involved war parties from Western Abenaki or eastern tribes who travelled some distance. The last incident in Falmouth occurred June 8, 1751 when a party of Indians from a Western Abenaki tribe killed John Burnal on the highway, shooting his horse out from under him.

Sources or further reading on this period of Falmouth History, see: Emerson W. Baker, “Finding the Almouchiquois: Native American Families, Territories, and Land Sales in Southern Maine,” Ethnohistory 51, no. 1 (Winter 2004); Samuel Purchas, “Description of Mawooshen,” Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes, vol. 19 (University Press, Glasgow, 1906); Christopher Levett, A Voyage into Nevv England, (London, 1628); David L. Ghere, “The ‘Disappearance’ of the Abenaki in Western Maine: Political Organization and Ethnocentric Assumptions,” American Indian Quarterly 17, no. 2 (Spring 1993); William D. Williamson, History of the State of Maine, vol 2 (Glazier, Hallowell, 1832).